Safeguard kids from the justice system Children Young People and Families

Safeguard kids from the justice system

VCOSS Submission to the CAG Review of the Age of Criminal Responsibility

Children under 12 couldn’t have seen Aladdin or the Lion King at the cinemas without a parent or guardian. Children under 13 need their parents’ permission to buy iPad apps. Children under 14 pay only $6 to see a footy game, a quarter of the price of adult tickets.

Yet children as young as 10 can and do experience the full force of the criminal justice system.

Children who become involved with the criminal justice system are extremely vulnerable. Child offending is closely linked to experiences of disadvantage. Before they offend, children have commonly already experienced trauma, abuse and neglect.

A punitive response to such behaviour effectively punishes those children for having a rough start in life, and in many cases can lead to a lifetime of criminality, disadvantage and exclusion. This means that children are punished long after being involved with the criminal justice system.

This response is failing vulnerable children.

If the system were set up differently, a child acting up could provide an opportunity for a positive intervention in their life. Behaviour that warrants the states attention could be met with care and support. This would give children the best possible chance to grow out of anti-social behaviours, strengthen their resilience and natural supports, and mature into prosocial adults.

This submission explores the questions posed by this review in two parts. Part one outlines why we should raise the age of criminal responsibility to 14. Part two of this submission provides a principles framework to underpin an integrated continuum of support to respond to child offending. A response which better connects the justice, social and universal service systems will enable a holistic response to the needs of the whole child to prevent harm and promote a safe community.

VCOSS would like to acknowledge the research and policy development undertaken by our members and sector colleagues which informed this submission, including the Smart Justice for Young People coalition, the Change the Record coalition, and Jesuit Social Services.

Raise the age of criminal responsibility

Recommendation

- Raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility to 14 in all circumstances

In all Australian states and territories, the minimum age of criminal responsibility is 10 years. This means children under the age of 10 years are considered incapable of committing an offence.

When a child older than 10 but younger than 14 commits an offence, the legal principle doli incapax is intended to provide a safeguard from the full force of the criminal law, and divert them from the criminal justice system.

The principle presumes that children aged 10 to 14 years are ‘criminally incapable’ because they cannot differentiate between behaviour that is merely naughty or criminal acts that are seriously wrong in the moral sense. Doli incapax provides that where a child does not understand the difference, they should not be held criminally responsible.

This presumption is rebuttable, with the onus on prosecution to prove in court that the child was capable of understanding the difference. If it is not rebutted, a child who offends may be found criminally responsible, and subject to full force of the criminal justice system, including imprisonment. In 2017 – 18, on any given day, there were 25 children under 14 on youth justice supervision in Victoria.[1]

Children should be protected from the force of the criminal justice system

Childhood is a distinct developmental stage. It makes sense that since children behave differently to adults, responses to their behaviour should be different too.

Well-established research underpins this. Children’s brains and their emotional, mental and intellectual maturity are still developing. Children seek rewards and short-term gains and they test limits and boundaries. They tend to be more susceptible to peer influence and risk-taking behaviour.[2]

If children act up, it is generally developmentally normal behaviour. They are not at a cognitive level of development where they are able to fully appreciate the criminal nature of their actions, or the potential consequences these actions give rise to.[3] Most child and young offending is episodic and transitory, and most children ‘grow out’ of offending behaviour as they mature.[4],[5]

It is often the most vulnerable and disadvantaged children who come to the attention of the criminal justice system for anti-social or offending behaviour. Children in the youth justice system are often survivors of abuse and neglect, have experienced the child protection system, homelessness, mental ill-health and more. They require a higher duty of care and more intensive interventions to meet their complex needs.[6]

Children involved with youth justice who have also experienced out-of-home-care have high rates of adverse experiences, including exposure to family violence, severe mental illness, traumatic deaths, drug use and household criminal justice involvement. The vast majority of these children have experienced neglect, and others have experienced physical abuse.

The current response to child offending effectively punishes children for having a rough start in life.

Doli incapax fails to safeguard children in the justice system

In recognition of the difference between children and adults, doli incapax is intended to provide protection from the criminal justice system.

Instead, it routinely fails to safeguard children. It is applied inconsistently and it can be very difficult for children to access expert evidence to prove in court that they are ‘criminally incapable’, particularly children in regional and remote areas.[7]

Further, by the time doli incapax is applied in court, the child has already been exposed to many stages of criminal procedure, including arrest, detainment and questioning.

This is unnecessarily criminogenic.[8] Research indicates that the younger a child is when they first come into contact with the justice system, the more likely they will become entrenched in the justice system.[9]

Once the age of criminal responsibility is raised to 14 years, doli incapax would be redundant.

Australia is out of step with international standards

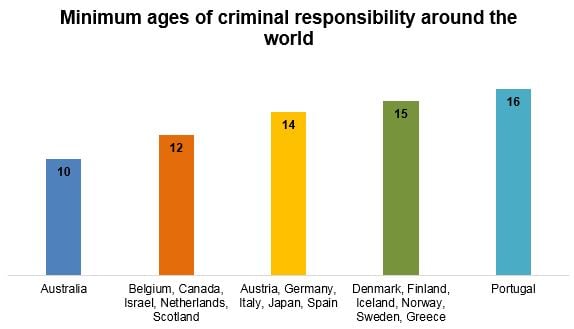

Australia has one of the lowest ages of criminal responsibility in the world. The median age of criminal responsibility worldwide is 14 years old.

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child has consistently said that countries should be working towards a minimum age of 14 years or older. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People has urged Australia to increase the age of criminal responsibility and stated that ‘children should only be detained as a last resort, which is not the case today for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children ’. Australia has been repeatedly criticised by the United Nations, most recently by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, for failing to reform the current minimum age of criminal responsibility.

Minimum ages of criminal responsibility around the world

Internationally, there are many examples of strong systems which support children who offend in meaningful and holistic ways. Looking around the world shows that raising the age of criminal responsibility, and therapeutic, welfare-based responses to young offending are possible.

For example, the best interests of the child are ensured through legislation in Sweden, Belgium and Spain. This enables interventions based on their needs, rather than a discrete response to offending behaviours.[10]

Prevent harm through appropriate responses to child offending

“The best way to protect the community is to invest in measures that prevent or interrupt the criminal pathways of children who would otherwise go on to commit a disproportionately high volume of youth crime. Measures such as enhanced early intervention and resources to rehabilitate young offenders are the best way to steer at-risk children away from a life of crime and protect the community in the long term.”

Sentencing Advisory Council, 2016[11]

Exposing children to the criminal justice system is harmful for the children involved, their families and the broader community.

If the age of criminal responsibility is raised to 14, it will protect children from the harmful, criminalizing effects of the justice system. For those children who offend under 14, there is a better way to respond to their offending, and build their emotional, social and mental wellbeing as a protective factor against their offending.

Recommendations

- Make detention the option of last resort for all children and young people

- Establish a principles framework to underpin responses to child offending

- Establish an integrated support continuum which addresses the causes and risks associated with child offending

- Adopt a justice reinvestment framework which ensures equitable funding for programs across the continuum and better integration between systems

Keep children away from prison

The best place for a child is with their family, their natural supports and their community.

Detention should be considered the option of last resort for all young people who offend. If the minimum age of criminal responsibility is raised to 14, then children under 14 would not be subject to detention.

Establish a principles framework to underpin responses to child offending

When a child demonstrates anti-social or offending behaviour, an opportunity emerges for appropriate social supports to make a positive intervention in their life. Responses to child offending should:

- Be child-centred, strengths based and trauma-informed. This includes responding to the holistic needs of the child, the underlying causes of their offending, and the needs of their family/natural supports;

- Comply with Australia’s international human rights obligations and the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities;

- Assume shared accountability and responsibility for offending, on the basis that the majority of child offending is a consequence of the failings of the institutions intended to support the child;

- Commit to addressing the overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island children and young people, CALD children and young people and young people who have been involved with out-of-home-care.

Establish an integrated continuum of supports for children and their families

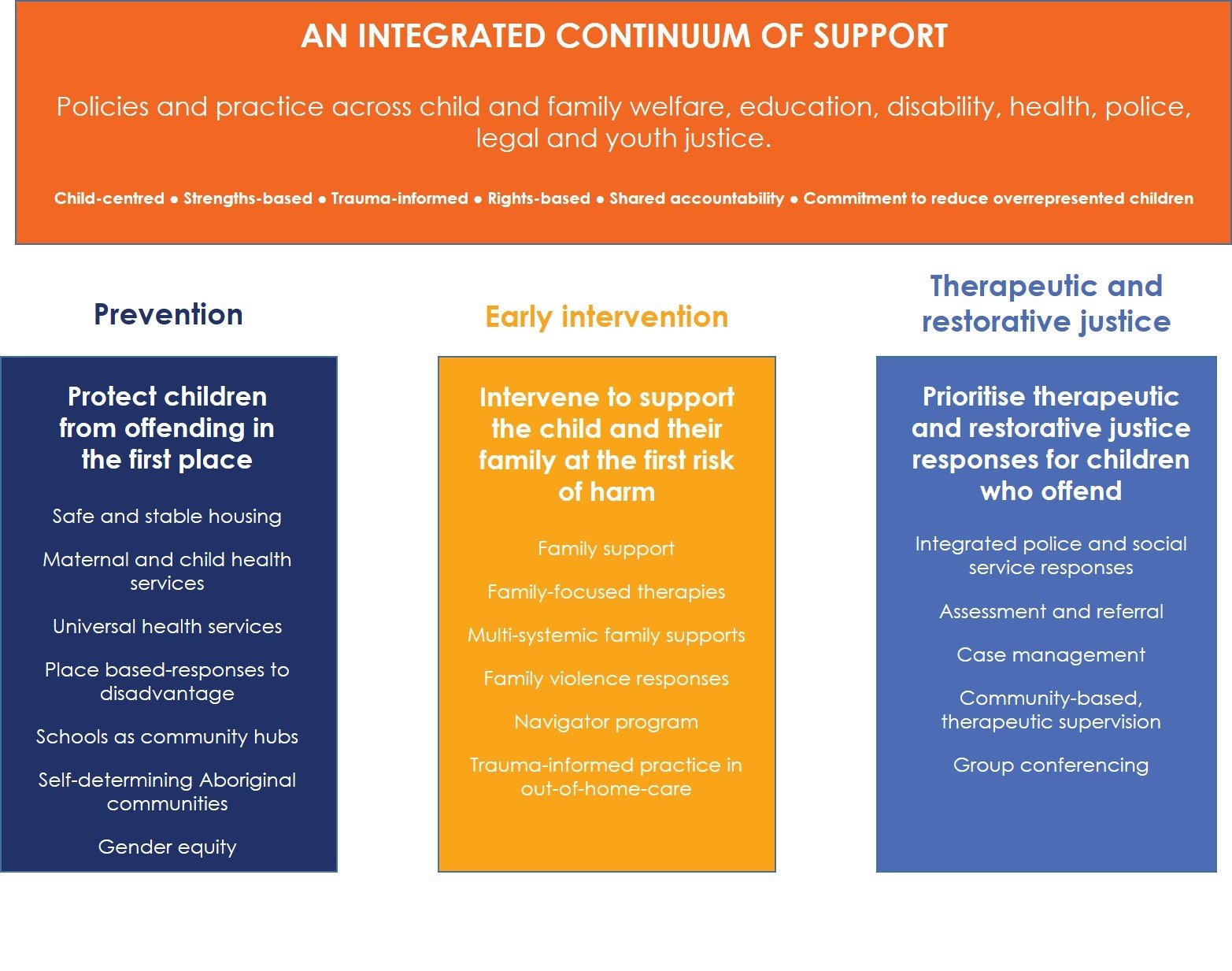

Supports should be provided across an integrated continuum, prioritizing and investing in prevention, early intervention and therapeutic and restorative justice as the most effective ways to respond to child and young offending/re-offending (see figure 1, p 12).

VCOSS believes that a system-wide response is required to tackle the systemic failings which underpin children’s involvement in the justice system. This integrates policies and practices across child and family welfare, education, disability, health, police, legal and youth justice systems. Community should be involved in design and implementation, including Aboriginal and culturally diverse communities, increases their effectiveness by addressing community-identified problems, drawing on existing community strengths and resources, and being culturally responsive.[12]

Reorienting responses to child offending from punitive to therapeutic will require a significant boost in funding for effective programs. This can be achieved by adopting a justice reinvestment framework which ensures equitable funding for programs across the continuum and better integration between systemsPresently, a significant barrier to protecting children from offending and reoffending is the lack of access to an appropriate program which meets their needs and is a proportionate response to the nature of their offending behaviour.

Enable and empower Aboriginal families, communities, and organisations to support children in culturally safe and appropriate ways

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are over-imprisoned, making up about 60 per cent of the young children in youth jails, despite being only about 5 per cent of the population (aged 10-17).[13] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to experience the ongoing impacts of colonisation, trauma, dispossession and racism. The over-incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people is both a result of this ongoing trauma, and exacerbates it.

In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the planning, design and implementation alternative justice responses should be community-led.

![]()

![]()

[1] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Youth detention population in Australia 2018, December 2018.

[2] For more, see Sentencing Advisory Council, Sentencing Children and Yong People in Victoria, April 2012; Chris Cunneen, Arguments for Raising the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility: Research Report, 2017; Queensland Family and Child Commission, The Age of Criminal Responsibility in Queensland, January 2017;

[3] Ibid.

[4] Lucinda Jordan and James Farrell, Juvenile Justice Diversion in Victoria: A Blank Canvas?, Current Issues in Criminal Justice, Volume 24 Number 3, March 2013.

[5] Kelly Richards, What makes juvenile offenders different from adult offenders?, Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice no. 409, Australian Institute of Criminology, February 2011.

[6] Australian Institute of Criminology, What makes juvenile offenders different from adult offenders? Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice, No. 409 February 2011.

[7] Kate Fitz-Gibbon and Wendy O’Brien, ‘A Child’s Capacity to Commit Crime: Examining the Operation of Doli Incapax in Victoria (Australia)’, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, December 2019.

[8] Parliament of Victoria, ‘Youth Justice in Victoria’, Research Papers, 2017.

[9] Chris Cunneen, Arguments for Raising the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility: Research Report, 2017.

[10] Jesuit Social Services, Raising the Age of Criminal Responsibility: There is a Better Way, October 2019, p4.

[11] Sentencing Advisory Council, Reoffending by Children and Young People in Victoria, Sentencing Advisory Council, Melbourne, December 2016.

[12] Kelly Richards, L Rosevear and R Gilbert, Promising interventions for reducing indigenous juvenile offending: Brief 1, Australian Institute of Criminology, March 2011.

[13] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Youth detention population in Australia 2018, December 2018.